Mount Vesuvius: The Devastation of Pompeii and Herculaneum

Explore the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD and its devastating impact on the ancient cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Discover how the eruption preserved these cities, offering unparalleled insights into Roman life, culture, and history. Learn about the recovery efforts led by Emperor Titus and the ongoing archaeological significance of these ruins.

HISTORIC EVENTSANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS

Michael Keller

11/18/202415 min read

In 79 AD the residents of Pompeii and Herculaneum Italy went about their daily lives, unaware of the catastrophic event that would soon unfold. The streets were filled with the usual bustle, traders peddling goods, children laughing as they played, and families carrying out their routines under the warmth of a seemingly ordinary day. Yet, amid this tranquility, something far more extraordinary was quietly taking shape, destined to disrupt the fabric of life in a way no one could foresee. Little did they know, the coming hours would mark a turning point, forever altering the fate of their cities and freezing their world in time.

The Height of the Empire

At that time, the Roman Empire was in the midst of the Pax Romana, a period of relative peace and stability that had lasted for more than a century. Emperor Vespasian had successfully solidified Roman control, and his son Titus was popular among the people, and a capable leader. [1] The Empire was not just peaceful, but also thriving in every sense. Trade routes across the Mediterranean were well-established, creating an economic boom that benefited all levels of society. Goods flowed freely, from the spices and silk of the East to the wine and grain of the West, creating a web of prosperity that tied the Empire together. [2]

This was a time of great cultural growth as well. Rome had long been a center of influence for art, literature, and philosophy, and by 79 AD, Roman culture was flourishing. [3] The grandiose architecture of the Empire's cities, from the colossal Colosseum in Rome to the lavish villas in Pompeii and Herculaneum, showcased the Romans' wealth and engineering ingenuity. Philosophers and poets filled the air with discussions of morality, the human experience, and the nature of the universe. The arts flourished, with frescoes decorating walls, marble statues adorning public spaces, and elaborate mosaics telling stories of gods, emperors, and warriors.

For the people of Pompeii and Herculaneum, life was full of promise and luxury. These cities were vibrant centers of trade, entertainment, and leisure, where the wealthy and the common folk alike could enjoy the fruits of Roman civilization. Bathhouses, theaters, and bustling markets dotted the landscape. People gathered in the forum to discuss the latest news, and Roman citizens lived under the protection of their Empire, enjoying a way of life that had been steadily evolving for centuries.

In the midst of all this prosperity, life seemed poised to continue its steady march of growth and success. The cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum thrived, their streets bustling with the promise of a bright future. Yet, beneath this calm surface, the forces of nature stirred, a quiet reminder that even in the most prosperous of times, the unexpected can alter the course of history. The sun shone brightly over the Roman world, but an invisible tension hung in the air, as if something, though unseen, was on the verge of changing everything.

The Earth Begins to Rumble

It was around 1 p.m. on that fateful day when the calm of Pompeii was shattered. From the distant peak of Mount Vesuvius, a faint plume of smoke began to rise, unnoticed by most. But as the minutes passed, that initial wisp of ash grew into something far more ominous. By now, the sky above Vesuvius had darkened, thick clouds of smoke and ash billowing from the summit, swirling like an angry beast roused from slumber. What began as a curious sight soon escalated into a spectacle of devastation. It became clear that something unimaginable was unfolding before the eyes of those living in the shadow of the mighty volcano.

In those critical moments, the people of Pompeii, just a few miles away, were unaware that the world as they knew it was about to end. The eruption was no slow, rumbling force; it came with the ferocity of nature’s raw power. Within minutes, a pyroclastic flow (a deadly, fast-moving cloud of superheated ash, gas, and rock) rushed down the slopes of Vesuvius, surging toward the cities with terrifying speed. Racing at up to 300 kilometers per hour, the flow was unstoppable, a deadly tide of molten destruction sweeping across the land. [4]

The temperature within the cloud soared to an unimaginable 800°C (1,472°F). It was a searing wall of death. [5] No one could outrun it, no one could escape its grasp. The dense, suffocating heat was fatal on contact, burning flesh and inhaling life from all who were unfortunate enough to be in its path. Those in the streets of Pompeii and Herculaneum, were now caught in the jaws of nature's fury. The cities, once teeming with life and culture, fell silent in an instant. A violent, ashen tide swept through the streets, reducing everything in its path to smoldering ruins.

The eruption’s shockwaves were felt far and wide, but it was in the destruction of these cities that the true horror lay. Pompeii and Herculaneum, bustling urban centers of the Roman Empire, were buried in an unthinkable volume of volcanic ash, pumice, and debris. Streets that had once been vibrant with the life of traders, citizens, and travelers became unrecognizable. Buildings that had stood for generations crumbled, their walls flattened under the weight of the relentless fallout. An estimated 16,000 to 20,000 people perished in those first moments, their lives extinguished instantly. In the wake of this catastrophic event, an eerie stillness would settle, and heroes would rise. [6]

The Long Recovery

In the immediate aftermath of the eruption, Emperor Titus took charge of the Roman government’s extensive recovery effort, focusing on restoring the affected cities, particularly Pompeii and Herculaneum. Public works projects were initiated with urgency, as entire sections of the cities had been buried under thick layers of ash, pumice, and debris. The destruction was staggering—buildings, roads, aqueducts, and civic structures that once stood as symbols of Roman prosperity had been obliterated. [12] The restoration efforts were monumental, involving not only the reconstruction of basic utilities but also the rebuilding of the intricate urban infrastructure that had defined the thriving lives of the cities. Titus’s personal involvement in overseeing the recovery efforts further reinforced the Empire's resilience and his compassion for his people. Laborers, craftsmen, and engineers were mobilized to work tirelessly, and their efforts not only helped to re-establish the cities but also provided a significant economic boost to the Empire. By creating jobs and reviving trade in the region, the recovery became a beacon of hope for the Empire’s future. [13]

The scale of the devastation was so vast that rebuilding the cities took many years, with entire neighborhoods and thousands of lives affected. The process was slow, but the Roman government’s swift action in organizing these efforts and ensuring the survival of the region underscored its ability to recover from such a catastrophic loss. Emperor Titus’s leadership during this crisis was critical in keeping the Empire intact. [14]

The long-term effects of the eruption were felt in more subtle ways. The recovery of the cities, combined with the discovery of Pompeii and Herculaneum centuries later, played a role in the cultural resurgence of the Roman Empire. New archaeological findings sparked a renewed interest in ancient Roman life and art, influencing subsequent generations. The cities’ ruins became an invaluable source of historical knowledge, offering unparalleled insights into the Roman way of life, architecture, and even social customs. [15]

Vesuvius is infamous for its catastrophic eruption in 79 CE, which buried the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. However, it wasn’t until 1738, during the Enlightenment, that excavations began to truly uncover the scale of the disaster. This was an age of scientific breakthroughs and social upheaval, and Vesuvius quickly captured the imagination of the era. It became a symbol of raw, untamed nature, a source of scientific curiosity, and a mirror for the intense political and emotional currents of the time. John Brewer takes us on a journey through the shifting seismic and social dynamics surrounding Vesuvius, revealing how travelers interpreted their awe-inspiring encounters with the volcano. Against the backdrop of revolutions and global conflicts, volcanic eruptions became potent political metaphors—embodying both revolutionary fervor and conservative fear. From Swiss mercenaries to English entrepreneurs, French geologists to Neapolitan guides, German painters to Scottish doctors, the slopes of Vesuvius teemed with individuals driven by passions, ambitions, and curiosities as volatile as the mountain itself.

Pliny the Elder

Amidst the chaos and devastation of the eruption, one figure stood out for his extraordinary bravery. Pliny the Elder. A distinguished commander of the Roman fleet and a respected scholar, Pliny had earned a reputation for his courage and resourcefulness. Although known for his extensive writings on natural history, astronomy, and the sciences, Pliny’s courage in the face of disaster was equally legendary. His fascination with the natural world, especially volcanic activity, would inform his decision to act. He had witnessed numerous volcanic eruptions during his career, but nothing could have prepared him for the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

At the time of the eruption, Pliny was stationed across the Bay of Naples at Misenum, where he commanded the Roman fleet. As soon as he learned of the eruption, he immediately gathered a fleet of ships and set sail with a small group of men to rescue those stranded by the disaster. His mission was to reach the towns along the coast, offering aid to anyone who could be saved from the fiery eruption. Pliny’s decision to take immediate action was driven by his sense of duty and his steadfast commitment to the Roman ideals of leadership and courage.

However, as he approached the shoreline, the situation rapidly deteriorated. The eruption unleashed an unprecedented storm of ash and pyroclastic material, blanketing the sea and the surrounding areas. Despite the peril, Pliny pressed forward, determined to carry out his rescue mission. He and his men faced increasingly dangerous conditions as the winds carried clouds of ash over the bay, and the temperature rose to unbearable levels.

Pliny's ship was forced to anchor off the coast of Stabiae (near modern-day Castellammare di Stabia), where he and his crew sought shelter. Yet, despite his resolute leadership, the volcanic effects soon caught up with him. The toxic fumes from the eruption, combined with the intense heat, overwhelmed Pliny. He collapsed and died, reportedly as a result of inhaling the poisonous gases, which suffocated him before he could complete his mission. Pliny the Elder's sacrifice, although heroic, was ultimately in vain in terms of his own survival. Yet, despite his death, his men, under the leadership of another officer, managed to continue the rescue efforts. It’s unclear how many individuals were saved in the wake of the disaster, but accounts suggest that some lives were spared as a result of Pliny’s courageous attempt to navigate through the peril. [7]

Though Pliny perished in the line of duty, his actions demonstrated remarkable leadership and selflessness. His death came as a tragic irony, as he had sought to save lives, only to lose his own to the very natural forces he sought to confront. His legacy, however, endured not just through the daring mission he led, but through the invaluable eyewitness account left by his nephew.

Pliny the Younger, who was in the area at the time, witnessed the eruption firsthand. He later documented the event in vivid detail, describing the darkness that fell over the region, saying, "A most dreadful and amazing sight... darkness came on, not like night, but like a black cloud" (Epistle VI, 16). His written account remains one of the most valuable resources for historians studying the eruption. [8]

The Empire responds

Emperor Vespasian, who reigned from 69 to 79 AD, was a pragmatic leader with a keen understanding of the vast and unpredictable Roman Empire. Recognizing the inherent risks that could threaten the stability of the Empire (from civil unrest to natural disasters), Vespasian worked diligently to strengthen its infrastructure and prepare for emergencies. He invested in the Empire’s physical infrastructure, focusing on roads, aqueducts, and public buildings. However, his most forward-thinking action was establishing a network to handle emergencies, a crucial step in ensuring that the Empire could respond effectively when disaster struck.

Though no definitive records pinpoint exactly why Vespasian placed such emphasis on disaster preparedness, his long-term vision for the Empire made it clear that he valued resilience above all. His initiatives included creating systems for swift responses to fires, famines, and civil disturbances. In doing so, Vespasian ensured that his successors would inherit not only a thriving Empire but also a framework to manage calamities, such as the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. This groundwork would play a pivotal role in the swift response to the volcanic disaster that would unfold just a few months after his death. [9]

When the eruption of Vesuvius struck, his son, Titus, was tasked with leading the recovery efforts. Titus inherited not only his father’s legacy of infrastructure but also his focus on compassion and efficiency in times of crisis. Upon hearing of the eruption, Titus immediately took charge, dispatching aid and relief teams to the affected cities. His response was swift, and his leadership was personal—he is said to have overseen rescue operations himself and provided significant financial support to the families of those affected. [10]

The emotional toll on the survivors of Pompeii and Herculaneum was immeasurable. Having witnessed the sudden destruction of their homes, families, and livelihoods, many were left in a state of profound shock and grief. The eruption not only stripped them of their possessions but also of the sense of security and normalcy that had once defined their lives. Families were torn apart, and countless individuals had lost loved ones, with some even finding the bodies of their relatives in the ruins. For those who survived, the psychological scars ran deep. The memory of the horrific events, of witnessing the ash clouds rising, of seeing their fellow citizens perish, haunted them long after the immediate crisis had passed. Many were forced to rebuild their lives from the ground up, often living in temporary shelters and grappling with the loss of their homes and everything they had known. This emotional devastation was a heavy burden, compounded by the uncertainty of what the future would hold in the wake of such a catastrophic event. [11]

Titus’s efforts were not just about logistics. In the wake of such devastation, he offered hope to his people, ensuring that survivors received the care they needed. Thanks to his father's foresight in preparing a disaster response system, Titus was able to act decisively, sending troops to search for survivors beneath the rubble, providing them with food and shelter, and organizing efforts to rebuild what had been lost. This seamless transition from Vespasian’s preparations to Titus’s leadership ensured the Empire could weather the aftermath of one of its most devastating natural disasters.

What do you think is the most significant lesson we can learn from Pompeii and Herculaneum's tragic fate?

Share your thoughts with us. For feedback or inquiries, email: contact@archivinghistory.com. We look forward to hearing from you!

Join Archiving History as we journey through time! Want to stay-tuned for our next thrilling post? Subscribe!

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok for captivating insights, engaging content, and a deeper dive into the fascinating world of history.

Source(s):

[1] McKay, John. A History of World Societies. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2011.

[2] Suetonius. The Twelve Caesars. Translated by Robert Graves. London: Penguin Classics, 2007.

[3] Beard, Mary. SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome. New York: Liveright Publishing, 2015.

[4] Scarpati, Claudio, and Giovanni Rolandi. "The 79 AD Eruption of Mount Vesuvius: An Analysis." Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 133, no. 3 (2004): 117-147.

[5] Baxter, Peter J., and Guido Zollo. "The Hazard of Pyroclastic Surges: The Mount Vesuvius Eruption." Nature Geoscience 2, no. 1 (2008): 46-49.

[6] Baxter "Pompeii after the Eruption," Archaeological Park of Pompeii. Accessed November 12, 2024. https://pompeiisites.org.

[7] Cooley, Alison E. Pompeii: A Sourcebook. New York: Routledge, 2013.

[8] Pliny the Younger. Letters and Panegyricus. Translated by Betty Radice. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1969.

[9] Levick, Barbara. Vespasian. New York: Routledge, 1999.

[10] Murison, Charles Leslie. Titus. London: Routledge, 2005.

[11] Berry, Joanne. The Complete Pompeii. London: Thames & Hudson, 2007.

[12] Lazer, Estelle. Resurrecting Pompeii. London: Routledge, 2009.

[13] Ling, Roger. Pompeii: History, Life & Afterlife. Gloucestershire: Tempus Publishing, 2005.

[14] Cooley, Alison E., and M. G. L. Cooley. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, 2014.

[15] Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew. Herculaneum: Past and Future. London: Frances Lincoln, 2011.

[16] Fiorelli, Giuseppe. Pompeii: An Archaeological Guide. Translated by Paul Arthur. Rome: L'Erma di Bretschneider, 2005.

[17] Jashemski, Wilhelmina F., and Frederick G. Meyer. The Natural History of Pompeii. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

[18] Allison, Penelope M. Pompeian Households: An Analysis of the Material Culture. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, 2004.

[19] Harris, Judith, and Dobbins, John. Pompeii Awakened: A Story of Rediscovery. London: I.B. Tauris, 2007.

[20] Zanker, Paul. Pompeii: Public and Private Life. Translated by Deborah Lucas Schneider. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998.

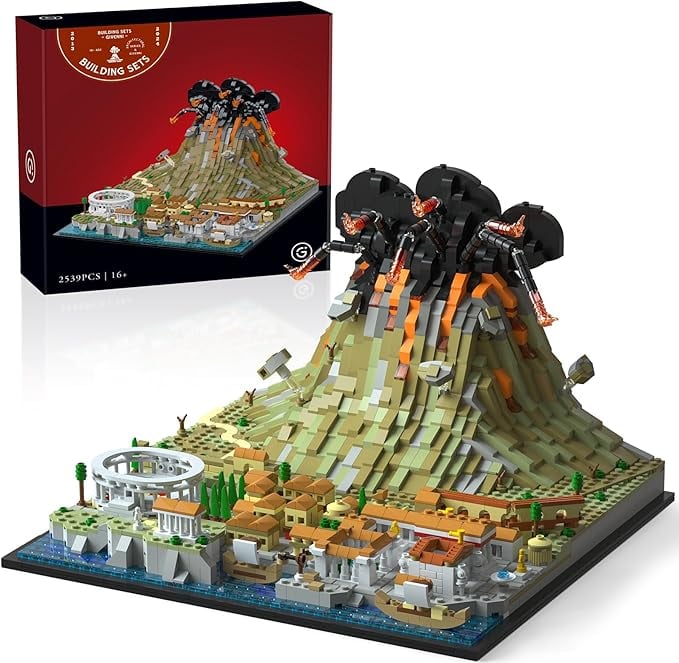

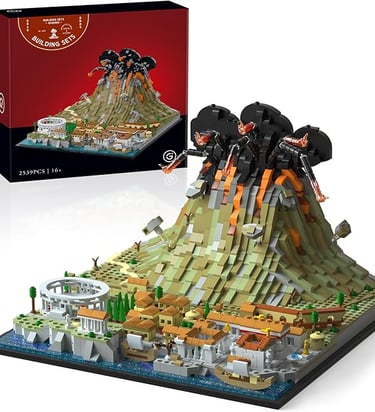

The Ancient City of Pompeii building set consists of 2539 pieces easy-installation parts. Detailed instructions are included.

Vesuvius is infamous for its catastrophic eruption in 79 CE, which buried the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. However, it wasn’t until 1738, during the Enlightenment, that excavations began to truly uncover the scale of the disaster. This was an age of scientific breakthroughs and social upheaval, and Vesuvius quickly captured the imagination of the era. It became a symbol of raw, untamed nature, a source of scientific curiosity, and a mirror for the intense political and emotional currents of the time. John Brewer takes us on a journey through the shifting seismic and social dynamics surrounding Vesuvius, revealing how travelers interpreted their awe-inspiring encounters with the volcano. Against the backdrop of revolutions and global conflicts, volcanic eruptions became potent political metaphors—embodying both revolutionary fervor and conservative fear. From Swiss mercenaries to English entrepreneurs, French geologists to Neapolitan guides, German painters to Scottish doctors, the slopes of Vesuvius teemed with individuals driven by passions, ambitions, and curiosities as volatile as the mountain itself.

Life Frozen in Time

The eruption didn’t just destroy; it preserved. Volcanic ash and pumice formed a protective layer over the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, encasing buildings, furniture, art, and even the bodies of the victims. Centuries later, archaeologists began excavating the preserved cities, uncovering the frozen moment. These bodies, encased in hardened volcanic ash, left behind molds of their forms, offering us an unparalleled look into the lives of ancient Romans. As archaeologists excavated, they found that the ash had preserved not just buildings and artifacts, but also the very positions and expressions of the people themselves. Carbonized bodies caught in mid-action were discovered, their final moments preserved as they went about their daily lives. People were still sitting at tables, others lying on their beds, and some, tragically, were caught trying to escape. These bodies provide a haunting and poignant snapshot of the final moments of the Roman citizens. [16]

Even their unfinished meals were preserved, offering a rare glimpse into what ancient Romans ate. Excavations have revealed food like dried fruit, fish, and even whole loaves of bread, suggesting a variety of ingredients and culinary habits. One of the most fascinating discoveries was the remains of a "fancy" meal. A banquet that included delicacies such as roasted meats, fish sauces, and preserved fruits, which would have been enjoyed by the wealthier citizens of Pompeii. [17]

The discovery of rich artifacts from the excavation further revealed the wealth and culture of these cities before their untimely burial. Beautiful frescoes, vibrant mosaics, and intricate jewelry were uncovered, such as gold rings, glassware, and decorative lamps. In Pompeii, the famous “Fresco of the Gladiators” was found, depicting athletic combatants in a highly detailed and dramatic scene. The preserved luxury of these finds gives us not only a window into the private lives of the ancient Romans but also insight into their artistic and social values. [18]

Rediscovery and Modern Significance

For over 1,700 years, Pompeii and Herculaneum lay hidden beneath volcanic ash, forgotten by the world. It wasn’t until the 18th century that excavations began, revealing these ancient cities in remarkable detail. The findings have been invaluable, offering an unparalleled snapshot of Roman society (its daily life, culture, and social structure), that no other source can match. [19]

Today, the sites of Pompeii and Herculaneum stand as invaluable sources of knowledge, offering insight not just into Roman society, but also into the intersection of nature, culture, and human resilience. These cities provide an extraordinary look at ancient urban life, including art, architecture, and even personal moments preserved in time. [20] The eruption may have marked the end for these cities, but their rediscovery ensures that their stories continue to shape the modern world’s understanding of the ancient past.

In the face of one of history’s most catastrophic events, the Roman Empire demonstrated resilience. The leadership of Emperor Titus, aided by the early efforts of Pliny the Elder, as well as the long-term recovery efforts, helped the Empire recover from the ashes. The eruption of Mount Vesuvius not only shaped the history of the Roman Empire but also left a legacy that continues to educate and inspire historians and archaeologists today. The ongoing study of Pompeii and Herculaneum reinforces the timeless importance of preserving and understanding the past to illuminate the present and future.