Timbuktu

Timbuktu was never a myth. Between the 13th and 16th centuries, it thrived as a West African hub of scholarship, trade, and culture. From the empire of Mansa Musa to the manuscript smugglers of 2012, this is the true story of a city that shaped intellectual history, and nearly lost it all. Explore the rise, resilience, and rediscovery of one of Africa’s greatest centers of learning.

HISTORICAL FIGURESEMPIRES AND DYNASTIESWARS AND BATTLES

Michael Keller

7/2/202515 min read

Timbuktu Was Not a Myth

For centuries, Timbuktu has been spoken of as if it were an illusion. A name thrown around to signify somewhere impossibly distant, forgotten, or fantastical. A place at the end of the earth.

But Timbuktu was never a myth.

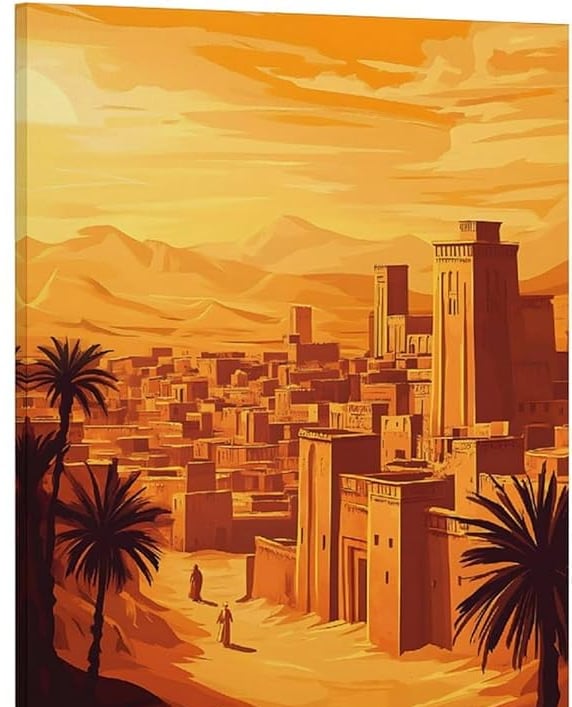

Located near the Niger River in present-day Mali, this West African city flourished between the 13th and 16th centuries as one of the world's great centers of learning, trade, and culture. [1] At a time when much of Europe was emerging from the shadows of feudalism, Timbuktu was building universities, hosting international scholars, and preserving knowledge that might otherwise have been lost.

It was a city of ink as much as gold.

The Rise of Timbuktu and the Mali Empire

Timbuktu began as a modest seasonal settlement in the early 12th century. Its founders were Tuareg herders, nomadic Berber-speaking people who traversed the Saharan trade routes for centuries. [2] What began as a temporary encampment, used primarily for grazing and trading during the dry season, gradually evolved into something more permanent.

The location was no accident. Timbuktu sat where the desert meets the river, offering a rare convergence of geographical advantages. To the north stretched the arid expanses of the Sahara, crossed by long-distance camel caravans carrying salt, textiles, and spices. To the south, the Niger River curved through fertile terrain, linking Timbuktu to agricultural zones and established inland cities like Gao and Djenné. [3]

This made the settlement a natural depot for goods, ideas, and people. As traders paused to rest, replenish supplies, and exchange wares, some settled permanently; transforming the encampment into a town. Over time, local markets formed. Wells were dug. Mud-brick buildings replaced tents.

By the mid-13th century, Timbuktu had grown prominent enough to attract the attention of the Mali Empire, then on the rise under Sundiata Keita, the empire’s founder and first great ruler. Known as the "Lion King of Mali," Sundiata forged a vast federation of cities and territories, uniting formerly independent kingdoms under a centralized, though flexible, system of governance.

Timbuktu was absorbed peacefully, drawn in not by conquest but by commerce, political leverage, and strategic necessity. Its incorporation into Mali brought new infrastructure, imperial protection for merchants, and access to Mali's growing gold economy. [4]

The city’s role began to shift. What had started as a stopover became a gateway, linking the Saharan trade routes with the imperial wealth of West Africa. And its rise was just beginning.

Mansa Musa and the Power of Knowledge

Mansa Musa ascended to power around 1312, at a moment of both opportunity and uncertainty for the Mali Empire. His predecessor, Abu Bakr II, is said by some Arab chroniclers to have vanished at sea in a failed expedition to explore the Atlantic. [5] Whether myth or fact, Musa’s rise to power marked a turning point: the transition from a prosperous kingdom to a globally known imperial force.

Though Musa inherited a thriving state, he reimagined its role in the world.

Mali’s wealth was unmatched. The empire sat atop one of the richest goldfields on Earth, especially in the regions of Bambuk and Bure, whose mines supplied a massive portion of the trans-Saharan gold trade. [6] But Musa understood something deeper: wealth alone does not build civilizations, institutions do.

He implemented a centralized taxation system that formalized Mali’s role as a commercial power. Caravans laden with salt, copper, kola nuts, and ivory were taxed at border towns. Foreign merchants were required to pay tribute to enter imperial markets. In return, they received protection and access to one of the most organized economies in medieval Africa.

He fortified trade routes with military outposts, secured river crossings, and ensured that banditry was punished swiftly. Markets flourished under his rule. Cities like Niani, Djenné, and Timbuktu grew in wealth and population. With the empire’s economy stable and revenue flowing, Musa turned his attention to something far more ambitious: the legacy of Mali.

Conflict, Conquest, and Continuity

By the late 15th century, the once-mighty Mali Empire had begun to fracture. Internal divisions, shifting trade routes, and external pressures chipped away at its cohesion. Into that vacuum rose a new power: the Songhai Empire, with its capital at Gao, located east of Timbuktu along the Niger River.

Under the leadership of Askia Muhammad I, Songhai not only absorbed much of Mali’s territory—it also continued and expanded its legacy of Islamic governance and education. [12] Timbuktu, now under Songhai control, remained a vital node in the empire’s administrative and intellectual life. Scholars, jurists, and scribes still walked its streets. Libraries still grew.

But the region’s wealth, and its symbolic power, had not gone unnoticed.

In 1591, the Moroccan Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur launched an ambitious and dangerous military expedition across the Sahara. His aim was clear: to seize control of the trans-Saharan trade network, particularly the gold routes flowing from West Africa into North Africa and the Mediterranean. But the Moroccans were not motivated purely by commerce. Al-Mansur also sought to assert Islamic authority and project imperial strength beyond his borders. [13]

He dispatched an army of a few thousand men, armed with arquebuses, early, matchlock firearms that gave them a decisive edge over the Songhai’s cavalry-based forces. The Moroccans were smaller in number but technologically superior. After a brief and brutal confrontation at the Battle of Tondibi, Songhai resistance collapsed. [14]

Timbuktu was soon occupied.

The aftermath was devastating.

Libraries were looted, either for valuable manuscripts or simply as spoils of war. Scholars, seen by some occupiers as potential dissenters, were imprisoned, exiled, or executed. A city built on discourse and learning was silenced by gunpowder and foreign rule.

But Timbuktu did not vanish.

Its resilience shifted form. With imperial structures shattered, families became the guardians of history. Manuscripts were hidden in trunks and clay jars. Lessons continued in secret. Religious leaders held small study sessions behind closed doors. Some knowledge was lost, but far more was protected.

The mosques reopened. Children were still taught to read. Copyists still inked pages, even if fewer than before.

And through famine, occupation, and political uncertainty, one truth endured:

The rhythm of scholarship never fully stopped. [15]

The 2012 Crisis and the Manuscript Rescue

In 2012, Timbuktu once again stood at the edge of destruction. But this time, it wasn’t imperial conquest or colonial neglect threatening the city, it was ideological warfare.

That year, a military coup in Mali’s capital, Bamako, toppled the central government. In the chaos that followed, the north fragmented. Armed Islamist factions, including Ansar Dine and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), exploited the power vacuum and swept into control. By summer, Timbuktu was under militant occupation.

To the outside world, the city fell quietly. But inside its walls, a different war was beginning. One not just for control, but for meaning.

The militants imposed a harsh interpretation of Sharia law, banning music, restricting movement, and inflicting brutal punishments for minor infractions. The mood in Timbuktu turned heavy with fear. Residents were ordered to destroy satellite dishes, women were forced to veil fully, and dissenting voices disappeared. The sense of daily life, of community rhythm, of cultural texture, was systematically dismantled. [16]

But the real targets were deeper.

They were symbolic.

The militants turned their rage on Sufi shrines, sacred burial sites that had stood for centuries as markers of Timbuktu’s spiritual tradition. These were not merely religious structures, they were expressions of a distinctly West African Islam, one rooted in mysticism, tolerance, and the quiet guidance of saints.

To the extremists, this was blasphemy. To Timbuktu’s people, it was a spiritual execution.

And then the libraries came under threat.

To the occupiers, the manuscripts represented more than books. They were proof. Proof that African Muslims had written about astronomy, law, science, and philosophy long before the rise of their rigid interpretation. The manuscripts told a different story, of a pluralistic, cosmopolitan, and deeply intellectual Islamic tradition. That made them dangerous.

Libraries were sealed off. Some were torched. Others were raided and tossed into piles like trash. In the eyes of the militants, erasing these texts was a way to rewrite history itself, to strip away all memory of a world that had once embraced knowledge, nuance, and debate. [17]

But this time, the people of Timbuktu did not wait for the world to help.

They mobilized themselves.

At the center of the resistance stood Abdel Kader Haidara, a lifelong guardian of manuscripts who had inherited a vast private collection from his father. He had spent decades traveling to remote villages, persuading families to relinquish precious texts so they could be preserved. He knew their value, not just academically, but emotionally. These manuscripts were heirlooms, lineages, and identities wrapped in leather and ink. [18]

When the militants arrived, Haidara realized: this wasn’t just a cultural emergency, it was a civilizational erasure.

He began reaching out to other librarians, archivists, and families. Quietly, a network of trust formed—built on whispered meetings, handwritten notes, and absolute discretion. The work required not only courage, but community: people who were willing to risk their lives with no promise of reward. Boatmen who ferried crates across the river by night. Shopkeepers who hid sacks beneath their floorboards. Elders who passed down codes and contacts only verbally.

The manuscripts were fragile. Many were centuries old, handwritten on brittle paper or gazelle skin, bound in handmade leather. If even one page tore or got wet, the damage was irreversible. Still, they were packed into rice sacks, wooden boxes, pillowcases, and crates, then smuggled out by car, canoe, motorcycle, or donkey cart, depending on the terrain and the presence of checkpoints. [19]

Some couriers traveled hundreds of miles through territory patrolled by militants.

No guards. No weapons. Just manuscripts, and the will to save them.

By the time French and Malian forces retook Timbuktu in early 2013, the resistance had already achieved the impossible: more than 350,000 manuscripts had been evacuated and hidden in safe houses across southern Mali. [20]

Not a single international organization had initiated the rescue.

No government ordered it.

It was done by the people.

This was not simply a salvage mission. It was a declaration.

A refusal to forget.

A refusal to allow centuries of African intellectual history to be reduced to ashes.

Most people think of Timbuktu as a far-off, forgotten place—but it used to be one of the world’s busiest and most important cities. It was packed with trade, culture, religion, and education, drawing visitors from across the globe. Mansa Musa, one of its most famous rulers, was so wealthy he’s still talked about today—and he even helped inspire Marvel’s Black Panther. Then there’s Mansa Sundiata, a real-life ruler whose nickname, the Lion King, might sound a bit familiar. While their stories may have been reshaped over time, their influence still shows up in modern pop culture.

So how did a place once compared to New York or London end up as a punchline for “the middle of nowhere”? Let’s uncover what really happened to Timbuktu.

He envisioned an empire that was not only wealthy, but wise. An empire respected by the great cities of Islam, Cairo, Mecca, Damascus, not just for its resources, but for its religious leadership, legal scholarship, and cultural sophistication.

So in 1324, he set out on the journey that would cement his place in global history: the hajj, a pilgrimage to Mecca, required of all Muslims with the means to undertake it. [7] But Musa’s hajj was no quiet act of devotion. It was a state procession on an imperial scale.

He traveled with an entourage estimated by some sources to number 60,000, including royal guards, merchants, slaves, wives, griots, and scholars. The caravan carried hundreds of camels, each laden with gold dust, textiles, and food. Musa reportedly gave gold so freely in Cairo that the market price of the metal collapsed and took over a decade to stabilize.

But the spectacle was not wasteful, it was calculated.

Musa was conducting soft diplomacy. In every city, he met with scholars, jurists, rulers, and merchants. He listened, observed, and took notes. He studied the architecture of mosques, the curriculum of madrasas, and the structure of Islamic courts. In Mecca and Medina, he prayed alongside imams from distant lands, forming bonds that would later guide his reforms.

He also purchased books, paid scribes, and recruited talent—men whose skills would be foundational to his plans for Mali. [8] Among them was Abu Ishaq al-Sahili, a poet and architect from al-Andalus (modern-day Spain), whose designs would later define a new style of Sahelian-Sudanese architecture. [9]

By the time Musa returned to Mali, he was no longer just a king, he was a statesman, carrying with him the tools of a different kind of empire.

His imports were not only artisans and teachers, but ideas. With them, he built mosques, legal courts, and madrasas. He restructured imperial governance using Islamic jurisprudence, professionalized the scribal class, and reoriented Mali’s intellectual compass toward the wider Muslim world.

But unlike many rulers who imposed foreign systems, Musa allowed these ideas to take root and grow organically, fusing with West African traditions and practices. He wasn’t trying to copy Cairo, he was building something uniquely Sahelian, yet globally respected.

He hadn’t just expanded Mali’s borders.

He rewired its cultural foundation.

And in doing so, he set the stage for what Timbuktu would become.

The Empire of Knowledge

What Mansa Musa set in motion evolved into more than a cultural flourishing it became a systematic intellectual revolution.

He didn’t merely fund scholars as ornaments of the court. He embedded knowledge into the function of the state. Madrasas were built with the intention of training not just theologians, but bureaucrats, legal advisors, and community leaders. Literacy in Arabic and proficiency in Islamic jurisprudence became qualifications for civic roles, from tax collection to legal mediation.

At the center of this transformation stood Timbuktu, which emerged as the empire’s flagship city of learning.

One of the most influential institutions was the Sankore Madrasah, a mosque-based university that grew into a decentralized network of master-teachers. [10] These scholars, or ʿulamāʾ, held court in open courtyards, shaded verandas, or private homes. Education was oral, textual, and deeply personalized. A single student might study under the same teacher for years, mastering not just the Qur’an, but grammar, logic, and law. Upon completion, the student would receive an ijazah, a license to teach and transmit knowledge within a defined intellectual lineage.

This wasn’t just about religious instruction. It was a way to create intellectual legitimacy, a traceable pedigree that proved the scholar's mastery and granted him standing within West Africa’s legal and religious networks.

Other cities such as Djenné and Gao also developed madrasas and manuscript libraries. But Timbuktu became the most renowned, not through royal decree, but because of its growing population of scholars, its access to long-distance trade, and its reputation for rigorous intellectual exchange.

Over time, knowledge itself became an industry.

Copyists learned to produce elegant scripts in Arabic and Ajami (African languages written in Arabic script). Local artisans specialized in ink-making, using powdered minerals, and leather binding, crafted from local hides. Manuscripts were copied with painstaking care and often featured marginalia, commentary written by students, teachers, or subsequent owners.

This turned each manuscript into a living document, passed between families, debated across generations.

And while religious texts were central, the curriculum went far beyond theology. Subjects included:

Astronomy, essential for both navigation and religious observance

Botany and pharmacology, using local and trans-Saharan plant knowledge

Mathematics, especially algebra and geometry, used in inheritance law and commerce

Ethics, law, and political theory, which formed the basis for civil life

Poetry, literature, and linguistics, both devotional and artistic in nature

By the 15th century, it’s estimated that Timbuktu housed hundreds of thousands of manuscripts, many written in Arabic, but also in Songhai, Tamashek, Fulani, and other regional languages. [11] This multilingualism reflects not only the diversity of the region, but the Africanness of its intellectual life.

Timbuktu wasn’t imitating the Islamic world, it was part of it. Connected through scholarship, trade, and correspondence, it stood as a peer to Fez, Cairo, and Mecca.

Letters traveled with merchants. Debates stretched across distances. Books were not just read, they were questioned, reinterpreted, and expanded.

And most importantly: this was not the passive adoption of foreign ideas.

It was African thought, African commentary, African intellectual tradition, speaking in its own voice, on its own terms.

That kind of courage forces a question:

Had you ever heard of Timbuktu's manuscripts before this?

If not, ask yourself, why not?

And what does it say about a society when it chooses to risk everything not for treasure, but for wisdom?

What are we doing to protect the knowledge we have now, about our own communities, our ancestors, our truths?

What other stories, buried in deserts, locked in vaults, hidden in footnotes; deserve this kind of attention and preservation?

Let us know. Your thoughts matter.

Because history isn't just what survives.

It's what we choose to save.

Share your thoughts with us. For feedback or inquiries, email: contact@archivinghistory.com. We look forward to hearing from you!

Join Archiving History as we journey through time! Want to stay-tuned for our next thrilling post? Subscribe!

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok for captivating insights, engaging content, and a deeper dive into the fascinating world of history.

Source(s):

1. “Timbuktu,” Encyclopedia.com, updated June 11, 2018, https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/timbuktu.

2. Tombouctou Manuscripts Project, “Timbuktu’s History,” University of Cape Town, accessed June 11, 2025, https://www.tombouctoumanuscripts.org/about-timbuktu/history.

3. “History of Timbuktu,” Wikipedia, last modified March 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Timbuktu.

4. “Mali Empire,” Wikipedia, accessed June 11, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mali_Empire.

5. “Mansa Musa,” Wikipedia, last modified May 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mansa_Musa.

6. Upfront Scholastic, “Mansa Musa: The $400 Billion Man,” Scholastic Classroom Magazines, 2018, https://upfront.scholastic.com/issues/2018-19/090318/mansa-musa--the--400-billion-man.html.

7. “The Cairo Gold Crash,” BBC Bitesize, last updated May 2019, https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/z7m2qp3.

8. “Mansa Musa,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mansa_Musa.

9. “Mansa Musa,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mansa_Musa.

10. “Sankoré Madrasah,” Wikipedia, last modified June 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sankor%C3%A9_Madrasah.

11. “Sankoré Madrasah,” Wikipedia, last modified June 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sankor%C3%A9_Madrasah.

12. “Askia Muhammad I,” Britannica, accessed June 11, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Muhammad-I-Askia.

13. “Battle of Tondibi,” Wikipedia, last modified April 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Tondibi.

14. “Battle of Tondibi,” Wikipedia, last modified April 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Tondibi.

15. “Timbuktu Manuscripts.” Wikipedia. Last modified May 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timbuktu_Manuscripts.

16. Has the Great Library of Timbuktu Been Lost?”, The New Yorker, January 29, 2013, https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/has-the-great-library-of-timbuktu-been-lost.

17. Naveena Kottoor, “How Timbuktu’s manuscripts were smuggled to safety,” BBC News, November 1, 2013, https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-22704960.

18. Joshua Hammer, “The Brave Sage of Timbuktu: Abdel Kader Haidara,” Innovators (National Geographic), April 21, 2014, https://www.nationalgeographic.com.

19. Tristan McConnell, “How Timbuktu Saved Its Books,” Harpers, February 2013, https://harpers.org/2013/02/how-timbuktu-saved-its-book/.

20. “Timbuktu Manuscripts,” Wikipedia, last modified May 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timbuktu_Manuscripts.

Artwork Home Office Decor Canvas Art 16x24inch(40x60cm) Frame-style

Most people think of Timbuktu as a far-off, forgotten place—but it used to be one of the world’s busiest and most important cities. It was packed with trade, culture, religion, and education, drawing visitors from across the globe. Mansa Musa, one of its most famous rulers, was so wealthy he’s still talked about today—and he even helped inspire Marvel’s Black Panther. Then there’s Mansa Sundiata, a real-life ruler whose nickname, the Lion King, might sound a bit familiar. While their stories may have been reshaped over time, their influence still shows up in modern pop culture.

So how did a place once compared to New York or London end up as a punchline for “the middle of nowhere”? Let’s uncover what really happened to Timbuktu.

What Timbuktu Teaches Us

Timbuktu challenges every myth we've been taught about Africa.

Not just the myth of the city itself, but the broader, more insidious myth that Africa has existed outside of history. That it was only ever a place of raw materials, not refined thought. A place of kingdoms, but not of universities. A place with stories, but not with books.

Timbuktu dismantles that narrative.

It reveals that the African continent was, and remains, a producer of ideas, science, law, and literature. That West Africa, in particular, was deeply engaged in global intellectual exchange, on its own terms.

It also dispels the notion that Islamic Africa was simply a product of foreign conquest. The Islam practiced and preserved in Timbuktu was localized, Africanized, and in many ways more inclusive than what existed in other parts of the Muslim world at the time. It blended Arabic text with African context. It translated theology into lived experience.

And perhaps most importantly, Timbuktu shows us this:

Empires fall. Armies come and go. But knowledge, if protected, can outlast them all.

In a world where history is often treated as disposable, the people of Timbuktu risked everything not for land, gold, or power, but for books. For the ideas within them. For the right to remember.

And that is no small act.

That is a form of resistance as profound as any revolution.

Because it says: Our history matters. Our voice matters. And we will not let it be erased.

When militants arrived with guns and fire, they found not silence, but resistance. Ordinary people, farmers, boatmen, teachers, librarians, stood between fire and parchment, and saved their memory with their hands.