The Life of Theodore Roosevelt

Discover Theodore Roosevelt's journey from a sickly child to a bold conservationist and war hero. Explore how he reshaped the U.S. presidency, reinvigorated national parks, and embodied the spirit of the "strenuous life."

HISTORICAL FIGURESHISTORIC EVENTSWARS AND BATTLES

Michael Keller

9/2/202514 min read

A Sickly Child with an Iron Will

Theodore Roosevelt was born on October 27, 1858, into a wealthy New York family with access to every privilege—except good health. From infancy, he suffered violent asthma attacks that left him gasping for air in the night, sometimes so severely that his parents feared they would lose him before morning.

His father, Theodore Sr., refused to accept a life of fragility for his son. He believed in building both moral character and physical strength, telling young Theodore, “You have the mind but not the body. You must make your body.” [1] Those words became a personal challenge.

Determined to conquer his weakness, Roosevelt began a self-imposed regimen—boxing in his family’s parlor, lifting weights, hiking in the countryside, and riding horses. It wasn’t instant transformation, but with every bead of sweat, the boy who once lay in bed fighting for breath was forging the iron will of a future president. The “strenuous life” wasn’t just a slogan—it was born in those wheezing, gasping nights.

By 1876, Roosevelt strode through the gates of Harvard as a tall, bespectacled young man whose energy matched his intellect. He was just getting started. [2]

From Harvard to Heartbreak

At Harvard, Roosevelt’s mind flourished. He studied natural history and political science, joined clubs, wrote for the student paper, and sparred in the boxing ring. Professors admired his curiosity; classmates were drawn to his enthusiasm.

But the most significant event at Harvard was meeting Alice Hathaway Lee. She was radiant—graceful, witty, with a laugh that could disarm even the most guarded heart. Their romance was swift and full of light. Roosevelt was smitten, and in 1880, they married. [3]

His political career began just as his personal life blossomed—winning a seat in the New York State Assembly in 1882. Roosevelt’s future seemed limitless. But in February 1884, joy gave way to unthinkable sorrow.

On Valentine’s Day, only hours after the birth of his first daughter, Alice, Roosevelt’s mother died suddenly of typhoid fever. Eleven hours later, his beloved wife succumbed to undiagnosed kidney failure. The double loss struck like a physical blow. In his diary that day, he drew a single, dark “X” and wrote, “The light has gone out of my life.” [4]

Reforging a Man

Shattered, Roosevelt walked away from both politics and New York society. He boarded a train headed 2,000 miles west—to the Dakota Badlands.

There, amid rolling prairies and jagged buttes, he bought cattle ranches and immersed himself in the harsh rhythm of frontier life. He learned to rope, brand, and ride for days under an endless sky. He hunted elk, chased rustlers, and once tracked down three thieves, holding them at gunpoint for forty hours until they could be jailed. [5]

The Badlands were not a retreat—they were a crucible. Here, Roosevelt reforged himself in the mold of the cowboy, the hunter, the lawman. The sickly child and grieving widower gave way to a man of resilience, self-reliance, and grit.

He also began to write—vivid accounts of the frontier that celebrated the land and the people who tamed it. [6] His words carried the dust, the danger, and the beauty of the West.

By 1886, he was ready to return east, remarrying his childhood friend Edith Carow. Together, they built Sagamore Hill on Long Island, a home filled with children, books, and the sound of the sea.

Teddy and the Bear

In November 1902, Roosevelt traveled to Mississippi at the invitation of Governor Andrew Longino for a bear hunt meant to settle a political dispute between the state’s rival hunting clubs. After days without success, guides cornered and tied a black bear to a tree for the president to shoot—a gesture meant to ensure his trip ended with a trophy.

Roosevelt took one look at the frightened, injured animal and refused. Calling the act unsportsmanlike, he ordered the bear to be put down humanely instead. [20] Word of the incident spread quickly, and within days, Clifford Berryman’s cartoon “Drawing the Line in Mississippi” appeared in the Washington Post. The image—depicting a small, wide-eyed bear—captured the public’s imagination.

In Brooklyn, toymaker Morris Michtom saw the cartoon and created a stuffed bear in Roosevelt’s honor, asking permission to call it the “Teddy Bear.” Roosevelt agreed, and soon the toys became a national sensation. [21]

What could have been a forgotten footnote in a hunting trip became a symbol of empathy. It softened Roosevelt’s public image, showing that the man who wielded the “big stick” also carried a quiet sense of mercy.

Big Stick Diplomacy and the Panama Canal

Roosevelt’s foreign policy was best captured in a proverb he often repeated: “Speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far.” [22] It was more than a slogan—it was his guiding principle. Roosevelt believed that skillful diplomacy should always be the first course of action, but that behind it must stand undeniable military strength.

To demonstrate this resolve, he dispatched the Great White Fleet—sixteen gleaming battleships painted in peacetime white—on a 14-month tour around the globe from 1907 to 1909. [23] The voyage wasn’t just a display of naval power; it was a statement that the United States had arrived as a world power and intended to stay.

One of Roosevelt’s most consequential acts was the securing of the Panama Canal. Determined to link the Atlantic and Pacific for both military and commercial advantage, he backed Panamanian independence from Colombia in 1903. Within weeks, the new Panamanian government signed a treaty granting the U.S. control of the Canal Zone. Construction of the canal was a monumental engineering triumph, cutting thousands of miles from maritime routes and reshaping global trade forever. [24]

In 1906, Roosevelt’s skill as a mediator shone when he brokered peace between Russia and Japan, ending the bloody Russo-Japanese War. For his efforts, he became the first American president awarded the Nobel Peace Prize—proof that his “big stick” could also be used to preserve peace, not just project power. [25]

Safaris, Politics, and the Bull Moose

When Roosevelt left the White House in 1909, he didn’t retreat quietly into private life. Almost immediately, he set off on a yearlong African safari sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution and National Geographic Society. Accompanied by his son Kermit and a team of naturalists, he traveled through present-day Kenya, Uganda, and the Congo, collecting thousands of animal and plant specimens for scientific study. His vivid accounts of the journey, published in newspapers and later as a book, kept him in the public eye and reinforced his image as the ultimate adventurer-president. [26]

But the call of politics proved irresistible. By 1912, Roosevelt had grown frustrated with his hand-picked successor, William Howard Taft, whom he felt had abandoned progressive reforms. Breaking from the Republican Party, he launched an independent bid for the presidency under the newly formed Progressive Party—a movement he declared was “fit as a bull moose,” giving the party its famous nickname. [27]

The campaign turned dramatic when, on October 14, 1912, an assassin’s bullet pierced his chest in Milwaukee. The would-be killer, John Schrank, was quickly subdued, but Roosevelt refused to head to the hospital before delivering his scheduled speech. Standing before the crowd with the blood-soaked manuscript in his pocket, he began: “Ladies and gentlemen, I don't know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot, but It takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose.” He spoke for an hour and a half before finally seeking medical care. [28]

Although Roosevelt ultimately lost the election to Democrat Woodrow Wilson, his fearless resilience during the campaign cemented his legend and inspired a generation of progressives to carry forward his vision.

The Final Years

Even after leaving the political stage, Roosevelt’s restless energy never dimmed. In 1913–14, he led the Roosevelt–Rondon Scientific Expedition into the uncharted Brazilian Amazon, co-discovering the “River of Doubt” (later renamed Rio Roosevelt). The journey nearly killed him—he suffered from malaria, infections, and severe weight loss—but it also produced important geographic and scientific findings.

Back home, he remained a prolific writer and commentator, publishing articles and books on history, politics, and nature. As World War I engulfed Europe, Roosevelt became a vocal advocate for American intervention, urging preparedness and national unity. His patriotism was deeply personal: four of his sons served in the war. In 1918, tragedy struck when his youngest, Quentin, a fighter pilot, was shot down over France. The loss broke his heart and visibly aged him.

On the night of January 6, 1919, Roosevelt died quietly in his sleep at Sagamore Hill, his beloved Long Island home. He was only 60. Vice President Thomas Marshall captured the sentiment of a nation when he quipped, “Death had to take Roosevelt sleeping, for if he had been awake, there would have been a fight.” [29]

Captivating History does a masterful job bringing the Roosevelt legacy to life. From Claes Martenszen van Roosevelt’s arrival in New Amsterdam in 1644 with little more than ambition, to the family’s rise in wealth through trade, real estate, and enterprise, this book traces the roots of one of America’s greatest dynasties. By the time Theodore Roosevelt was born in 1858, the Roosevelts were among the nation’s elite—yet his father ensured Teddy never took privilege for granted. With vivid detail and engaging storytelling, Captivating History makes the Roosevelt journey feel both inspiring and unforgettable.

Climbing the Political Ladder

When Roosevelt returned from the Badlands, he wasn’t just a man rebuilt in body—he carried with him the grit of the frontier and an impatience for political corruption. Appointed to the U.S. Civil Service Commission in 1889, he charged in like a reforming whirlwind, challenging the entrenched spoils system. Washington insiders expected him to play along; instead, he dismantled patronage networks and demanded merit-based hiring, earning both admiration and enemies. [7]

In 1895, he took on a new challenge as New York City’s Police Commissioner—a job most saw as a political dead end. The NYPD was riddled with bribery, vice, and cronyism. Roosevelt walked the city streets at night, flashlight in hand, catching sleeping officers and corrupt beat cops. He instituted physical fitness standards, modernized procedures, and insisted the law be enforced equally, whether in a Bowery saloon or an uptown parlor. His fearless approach was loud, visible, and impossible to ignore. [8]

By 1897, his reputation as a relentless reformer caught the eye of President William McKinley, who appointed him Assistant Secretary of the Navy. Roosevelt poured himself into the role—modernizing ships, stockpiling coal, and advocating for a powerful fleet to project America’s strength abroad. But when tensions with Spain escalated over Cuba’s fight for independence, Roosevelt couldn’t stomach the thought of waging war from behind a desk. [9]

The Rough Riders

In the spring of 1898, Roosevelt resigned from the Navy Department and set out to raise a volunteer cavalry regiment unlike anything the U.S. Army had ever seen. It would be a fusion of worlds: Ivy League football stars, Texas Rangers, Native American sharpshooters, frontier cowboys, and New York policemen. Roosevelt trained alongside his men, riding, drilling, and shooting under the blistering sun. His enthusiasm was contagious, his energy tireless. [10]

When the Rough Riders shipped out to Cuba, they stepped into an unforgiving theater of war—suffocating heat, swarms of mosquitoes, tropical disease, and the constant threat of Spanish fire. The defining moment came on July 1, 1898, during the Santiago campaign. Roosevelt, wearing a fringed buckskin shirt and spectacles, mounted his horse and charged up Kettle Hill, pistol blazing. The climb was steep, the air thick with gunpowder, and bullets hissed past in lethal streams. His men followed, inspired by his refusal to take cover. [11]

Reaching the summit, Roosevelt didn’t pause—he pressed forward toward the higher ground of San Juan Hill, this time on foot. By late afternoon, the American flag flew over the heights. The victory, though costly, was decisive. It secured the U.S. foothold in Cuba and elevated Roosevelt from reformer to national war hero. [12]

When he returned stateside, the press couldn’t get enough of him. Newspapers painted him as the embodiment of courage, grit, and patriotic vigor. Within months, he was swept into the governor’s mansion in Albany, his political trajectory now unmistakably aimed toward the presidency. [13]

From Second-in-Command to Commander-in-Chief

In 1900, Republican party bosses—frustrated by Roosevelt’s reformist zeal as New York governor—pushed him onto the national ticket as McKinley’s vice-presidential nominee. It was meant to be a quiet political exile; the vice presidency was, at the time, a largely ceremonial role with little real power. [14] Roosevelt accepted, campaigning with his usual vigor and drawing crowds far larger than anyone expected.

The year was 1901. Six months into McKinley’s second term, the president attended the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York—a showcase of industry, culture, and American progress. There, in the Temple of Music pavilion, an anarchist named Leon Czolgosz approached during a public reception. Concealing a pistol beneath a handkerchief, he fired two shots into McKinley’s abdomen. [15]

At first, optimism prevailed. McKinley seemed to rally after surgery, but infection set in. Eight days later, he succumbed to gangrene. The nation mourned, stunned by the sudden violence. On September 14, 1901, Theodore Roosevelt—summoned from a family vacation in the Adirondacks—was sworn in at the Wilcox Mansion in Buffalo. At just 42 years old, he was now the youngest president in U.S. history, propelled into power by tragedy and a world watching to see what he would do next. [16]

A New Kind of Presidency

From his first days in office, Roosevelt refused to be a passive caretaker of the presidency. He saw the office not merely as an administrative role, but as a “bully pulpit”—a platform from which a leader could rally the public and drive national reform. His philosophy, which he called the “Square Deal,” rested on a simple but radical principle for the era: fairness for all, whether you were a laborer in a mine, a consumer in the marketplace, or a farmer working the land. [17]

Roosevelt took on the might of the railroad monopolies, reviving enforcement of the Sherman Antitrust Act and forcing powerful corporations like the Northern Securities Company to break apart. He championed landmark Pure Food and Drug laws, spurred by public outrage over unsafe products and unsanitary conditions in the meatpacking industry. His push for stricter meat inspection standards wasn’t just bureaucratic tinkering—it was a direct stand against industries that put profit over public safety.

Through these actions, he expanded the role of federal regulation, rejecting the notion that government should simply step aside and let markets rule unchecked. For Roosevelt, the presidency was a moral trust, and its first duty was to protect ordinary Americans from the abuses of concentrated wealth and power. [18]

Conservation Crusader

Roosevelt’s passion for the wild was more than a personal hobby—it was a driving force behind his presidency. The vast plains of Dakota, the deep forests of the West, and the rugged mountain trails he had once ridden all left their mark on him. He understood, perhaps better than any leader before him, that America’s natural treasures were finite. If they were left to the unchecked appetites of industry, they would vanish.

During his presidency, Roosevelt acted with unprecedented ambition, placing more than 230 million acres under federal protection. He created five national parks, established 150 national forests, and designated 51 bird sanctuaries, 18 national monuments, and four game preserves. [19] The 1906 Antiquities Act became one of his most potent tools, allowing him to preserve landmarks of both natural beauty and cultural heritage—from the sweeping vistas of the Grand Canyon to the ancient cliff dwellings of the Southwest.

For Roosevelt, conservation was never about clinging to a romanticized past. It was about responsibility. He saw the land as a trust, held not for the present alone but for all the generations yet to come. In his own words, “The nation behaves well if it treats the natural resources as assets which it must turn over to the next generation increased, and not impaired, in value.”

Today, as we face our own tests of leadership, integrity, and vision, we might ask ourselves: Are we willing to lead with the same mix of strength, humility, and unshakable purpose—or will we leave that strenuous life to history?

For feedback or inquiries, email: contact@archivinghistory.com. We look forward to hearing from you!

Join Archiving History as we journey through time! Want to stay-tuned for our next thrilling post? Subscribe!

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok for captivating insights, engaging content, and a deeper dive into the fascinating world of history.

Source(s):

1. Edmund Morris, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt (New York: Random House, 1979), 3–7.

2. Kathleen Dalton, Theodore Roosevelt: A Strenuous Life (New York: Vintage, 2002), 12–18.

3. David McCullough, Mornings on Horseback (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1981), 204–10.

4. Morris, Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, 131–37.

5. McCullough, Mornings on Horseback, 288–93.

6. Dalton, Strenuous Life, 62–66.

7. Morris, Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, 173–78.

8. Dalton, Strenuous Life, 97–104.

9. Morris, Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, 189–94.

10. Edmund Morris, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt (New York: Random House, 1979), 328–34.

11. Theodore Roosevelt, The Rough Riders (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1899), 112–18.

12. Kathleen Dalton, Theodore Roosevelt: A Strenuous Life (New York: Vintage, 2002), 167–71.

13. Morris, Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, 352–57.

14. Dalton, Strenuous Life, 201–5.

15. Morris, Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, 379–84.

16. David McCullough, Mornings on Horseback (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1981), 382–87.

17. Dalton, Strenuous Life, 225–32.

18. Morris, Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, 401–8.

19. Douglas Brinkley, The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (New York: Harper, 2009), 331–42.

20. Edmund Morris, Theodore Rex (New York: Random House, 2001), 24–28.

21. Michael Patrick Cullinane, Teddy Roosevelt’s America: A Cultural History of the Early 20th Century (New York: Routledge, 2017), 63–66.

22. Theodore Roosevelt, An Autobiography (New York: Macmillan, 1913), 524.

23. Kathleen Dalton, Theodore Roosevelt: A Strenuous Life (New York: Vintage, 2002), 367–72.

24. David McCullough, The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870–1914 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1977), 445–51.

25. Morris, Theodore Rex, 154–58.

26. Douglas Brinkley, The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (New York: Harper, 2009), 523–29.

27. Dalton, Strenuous Life, 412–18.

28. Morris, Colonel Roosevelt (New York: Random House, 2010), 218–24.

29. Candice Millard, The River of Doubt: Theodore Roosevelt’s Darkest Journey (New York: Doubleday, 2005), 89–96.

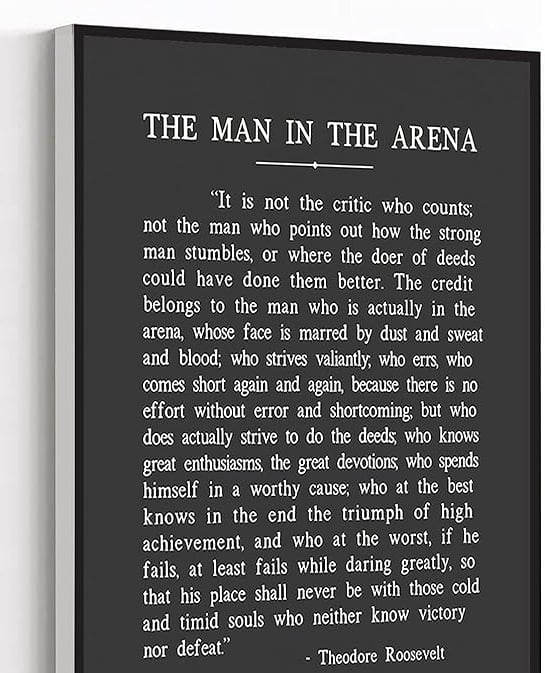

The Man In The Arena Metal Print,Theodore Roosevelt Quote

Captivating History does a masterful job bringing the Roosevelt legacy to life. From Claes Martenszen van Roosevelt’s arrival in New Amsterdam in 1644 with little more than ambition, to the family’s rise in wealth through trade, real estate, and enterprise, this book traces the roots of one of America’s greatest dynasties. By the time Theodore Roosevelt was born in 1858, the Roosevelts were among the nation’s elite—yet his father ensured Teddy never took privilege for granted. With vivid detail and engaging storytelling, Captivating History makes the Roosevelt journey feel both inspiring and unforgettable.

Why Roosevelt Still Matters

Theodore Roosevelt didn’t simply hold the office of president—he redefined it. He expanded the role into one of moral authority and decisive action, proving that leadership could be both forceful and principled. He confronted monopolies that threatened democracy, carved conservation into the nation’s conscience, and made the United States a visible, respected voice on the world stage.

Yet Roosevelt was full of contrasts. He was a man of privilege who championed the working class, a soldier who sought peace, and a political bruiser who could still inspire unity. He embraced both grit and grace, understanding that to lead meant to serve, and to serve meant to stand firm even when the fight was costly.

From the asthmatic child gasping for breath in a Manhattan townhouse to the larger-than-life figure who charged up San Juan Hill and preserved the Grand Canyon, Roosevelt’s life was proof of his own creed—that a strenuous life, lived with courage and conviction, is the surest path to meaning.