The Battle of Adwa

Discover the epic story of the Battle of Adwa, where Ethiopia defied European colonization in 1896. Explore how Emperor Menelik II and Empress Taytu united a diverse empire, defeated a modern Italian army, and redefined African resistance. A powerful narrative of strategy, sovereignty, and survival.

WARS AND BATTLESHISTORIC EVENTSHISTORICAL FIGURES

Michael Keller

8/2/202517 min read

The Battle of Adwa: Ethiopia’s Stand Against Empire

Mountains carved in stone. A people woven together by ancestry, terrain, and purpose. In 1896, the Ethiopian highlands—silent and vast—became the stage for one of the most decisive anti-colonial victories in world history. [1]4

But the story does not begin with gunfire or flags.

It begins with maps drawn in foreign capitals. With diplomats signing papers behind velvet doors. With the quiet confidence of an empire that believed Africa could be divided like land on a ledger.

In European salons and colonial ministries, Ethiopia was assumed to be a formality—an obstacle to be managed, not feared. Few understood the complexity of the state they were about to confront: a kingdom older than many of their own, with lineages of kings, deeply rooted spiritual authority, and a political system that valued both steel and scripture.

Ethiopia had seen invaders before. It had buried them before, too.

Yet in the closing years of the 19th century, as the "Scramble for Africa" reached a fever pitch, this ancient kingdom stood at a crossroads. Foreign armies loomed on its doorstep. Treaties arrived inked in two languages—saying different things. And behind every promise of friendship was a shadow of possession.

What unfolded next was not inevitable.

This is not just the story of a single battle.

It is the story of a kingdom that stood alone while empire after empire—from Lisbon to Istanbul to Rome—sought to bend it to submission.

And at Adwa, Ethiopia said no.

A Land Shaped by Stone and Spirit

Ethiopia is a land of contrasts—where the earth seems to rise up and defend itself. From the wind-scoured ridgelines of the Simien Mountains to the blistering salt flats of the Danakil Depression, the terrain resists taming. Rainfall clings to the high plateaus. Volcanic rock juts from river valleys like sentinels. The land is beautiful, but never passive.

Here, borders were not drawn by colonizers—they were carved by rivers, held by blood, and defended by memory.

Long before European empires arrived with their maps and manifestos, Ethiopia had already built a world of its own. It had kings who claimed descent from Solomon and Sheba, and manuscripts copied in monastic scriptoria high above the clouds. [2] Trade caravans moved through cities centuries old. In these highlands, time did not follow European clocks.

To outsiders, especially in the 19th century, it all looked disjointed. They saw provinces, not polity; dialects, not discourse. Some dismissed it as a land of tribalism, fractured by geography and tradition.

But that was a misread.

What looked like fragmentation was, in many ways, flexibility. Ethiopia's survival had never depended on uniformity. It had endured because of its ability to adapt, to merge lineage and religion, to turn mountains into fortresses and diversity into strength.

And unlike most of the continent, it had never been claimed.

Not by Rome. Not by the Ottomans. Not by the flags now sweeping across Africa from European capitals. [3]

It stood alone—not untouched by the world, but never owned by it.

And as the 19th century drew to a close, the world was about to be reminded of just how firmly it intended to remain that way.

A Ridge of Reckoning: The Battle of Amba Alagi

- December 7, 1895 [14]

The clash began in the mountains.

The Italians had marched deep into the Tigrayan highlands, believing their modern rifles, artillery, and strict formation would win the day. Their commander, Major Pietro Toselli, had entrenched his force at Amba Alagi, a towering ridgeline that overlooked one of the few viable roads through the region. Toselli believed elevation was dominance. From up high, he saw only tactical advantage.

But elevation in Ethiopia can be deceiving. The land hides its defenders well.

On the other side, Ethiopia had sent one of its most seasoned commanders—Ras Makonnen Wolde Mikael—a man as skilled in diplomacy as he was in war. Makonnen, a veteran of multiple campaigns, knew the terrain intimately. His forces moved swiftly and in silence, navigating goat trails and side gullies that European maps had missed entirely.

Makonnen’s force was not alone. He coordinated with Ras Welle Betul (Taytu’s own brother), encircling the Italians in a pincer movement that would close like a noose. [13]

At dawn, Ethiopian scouts struck first, testing the Italian defenses. Then came the full force—a coordinated assault from multiple angles. The Italians attempted to fall back to higher ground, but found themselves flanked. Their artillery, meant for open field combat, was nearly useless in the tight, broken terrain.

Major Toselli tried to regroup. He gave the order to retreat—but the path was already blocked.

Within hours, the Italian lines collapsed. Men fell in the confusion, trampled by their own or struck from above. Ethiopian fighters surged forward with gunfire and blades. It’s estimated that over 2,000 Italian soldiers were killed or captured. Toselli himself was shot while trying to rally his men. [16]

For the Italians, it was more than a defeat. It was a rupture in the myth of European invincibility. For years, colonizers had swept through African territories with impunity, assuming that outdated weapons and “primitive” tactics could not stand against organized European might.

Amba Alagi proved otherwise.

And Ras Makonnen’s name—already respected—took on new gravity. Though few knew it then, his young son, Lij Tafari Makonnen, was watching. [17] That boy would grow up to become Haile Selassie, emperor and future symbol of resistance in Ethiopia’s next war against fascist Italy. [18]

Amba Alagi wasn’t the end.

It was only the opening salvo—a thunderclap warning of what was still to come.

The Fortress Cracks: Siege of Mekelle

- January 6, 1896

After the rout at Amba Alagi, the Italians pulled back to consolidate their lines. They dug in at Mekelle, a hilltop fortress built of stone and confidence—designed to project strength and stability in northern Ethiopia.

Inside, over 1,200 Italian troops took position behind thick walls, sandbags, and artillery placements. They had food, ammunition, and the high ground. They believed the fort would hold. [19] They believed the Ethiopians would come crashing against its gates and break.

But Menelik II was not interested in a frontal assault. He had watched European wars. He had studied fortifications. He understood the cost of siege warfare—and he intended to win this one without wasting Ethiopian blood.

Instead of cannons, Menelik brought strategy. He sent scouts to choke the roads leading to Mekelle. He ordered the fort’s water supply cut off. Streams were diverted. Wells were blocked. Couriers carrying pleas for relief were intercepted. And then he waited.

Inside the walls, time turned against the Italians.

What began as a test of patience became a contest of endurance. Days passed. Then a week. Then two. Italian soldiers began rationing water by the mouthful. Horses collapsed. Dysentery spread. The men grew weak—not from bullets, but from thirst.

Ethiopian troops, encamped just beyond rifle range, remained silent. No rushes. No battle cries. Just a siege tightening like a vise.

By the fourteenth day, the Italian garrison surrendered.

But what came next shocked Europe far more than the surrender itself.

Rather than slaughter or imprison the men, Menelik let them go. They were allowed to keep their weapons, march out with their officers, and return to their lines with honor intact. [20]

To European audiences, this made no sense. This was supposed to be the behavior of a vengeful “tribal” king. But Menelik was playing a longer game. This act of mercy wasn’t weakness—it was power, expressed through restraint.

Newspapers in Paris, London, and St. Petersburg reported on the Ethiopian emperor who had shown more civility than the colonizers who sought to tame him.

Menelik didn’t just win a battle at Mekelle.

He won moral ground, in a war where perception would soon matter almost as much as victory.

And while the fortress lay quiet once more, the war was far from over.

The Noose Tightens: Endagabatan

- February 22, 1896

By February 1896, the Italians were no longer moving with confidence. They were marching with hesitation.

General Oreste Baratieri, commander of the Italian forces in Eritrea, had miscalculated from the start. He assumed Ethiopia would fracture under pressure. Instead, he found himself facing a unified and determined empire that refused to rush—but never stopped advancing. [21]

And now, it was closing in.

At Endagabatan, a rugged stretch of terrain marked by thorny ridges and winding gullies, an Italian column moved to reposition. Baratieri was trying to probe the Ethiopian perimeter, searching for soft spots. [22] But instead of finding a gap, his men found resistance in motion.

Ethiopian scouts had been tracking them for days. Ras Mikael of Wollo, one of Menelik’s most experienced commanders, saw the opportunity and struck.

What followed was not a set-piece battle—but a sustained campaign of disruption.

Ethiopian fighters—many of them cavalry and skirmishers—launched rapid-hit assaults on Italian outposts, convoys, and messengers. Supply mules were cut down. Ammunition carts overturned. Food wagons were seized or destroyed. Every attempt the Italians made to stabilize their forward positions was met with sudden fire, sudden steel, and then silence.

It was classic highland warfare: mobility over formation, terrain over technology.

The Italians responded by tightening their lines and retreating into more defensible positions—but this only made things worse. Baratieri’s men were now spread thinner than ever, unable to scout freely or move supplies between encampments without risk. Messages were delayed. Reinforcements hesitated. Morale cracked.

For the Ethiopian command, Endagabatan wasn’t about territory—it was about pressure. About exhausting the enemy. Bleeding him slowly.

By the end of the engagement, there was no dramatic surrender or captured fort. But the strategic damage was done. [23]

The Italians had been forced on the defensive once more, their movements now reactive, not decisive. And Menelik’s forces? They were still gathering—still waiting—still watching from the high ground.

Endagabatan didn’t make headlines in Europe. It lacked spectacle.

But it sharpened the blade for what was coming next.

And in war, sometimes it’s not the loudest battles that decide the outcome—

—it’s the quiet ones that leave your enemy bleeding before the final blow.

In 1896, Ethiopia did what no other African nation had—defeated a European imperial army on the battlefield. The Battle of Adwa shattered the myth of inevitable colonization, humbling Italy and electrifying the African diaspora. In The Battle of Adwa: African Victory in the Age of Empire, Raymond Jonas offers a vivid, multi-continent account of this seismic moment. With figures like Emperor Menelik II, Empress Taytu, and Swiss advisor Alfred Ilg at its center, the book explores how strategy, diplomacy, and vision turned Ethiopia into a global symbol of resistance—challenging white supremacy long before decolonization took root.

Menelik and Taytu: Empire in Partnership

In the late 19th century, Ethiopia stood on the edge of change.

Foreign traders arrived in the highlands with rifles, telegram cables, and silver coins. Missionaries preached. Diplomats whispered. Steamships in the Red Sea moved closer to the Ethiopian frontier. Borders that once felt like natural shields—mountains, deserts, rivers—now seemed porous, vulnerable to the ambitions of distant empires.

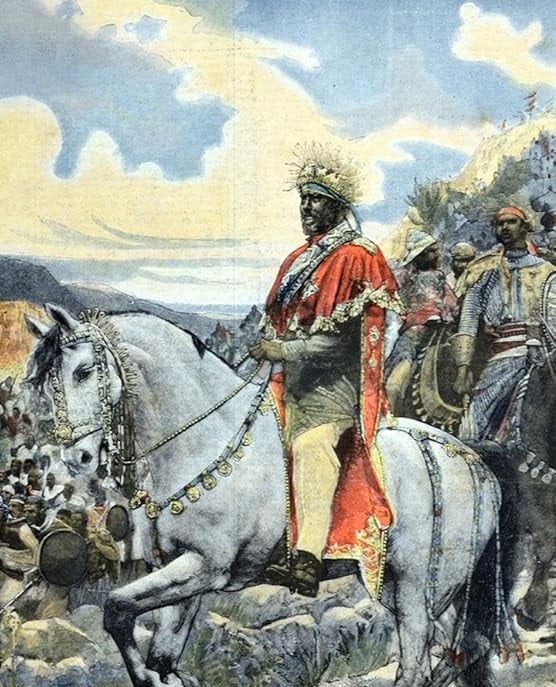

Into this moment stepped Menelik II, crowned Emperor in 1889, ruler of the powerful kingdom of Shewa, and a statesman unlike many of his contemporaries. He had watched other African rulers fall—some conquered, some co-opted, some erased. He intended to be none of these. [4]

Menelik was not a warrior-king alone. He was a calculator. He studied weapons shipments, European politics, regional loyalties. He understood that survival wouldn’t come from resistance alone—it would require roads, telegraph lines, alliances, and timing. He was both builder and broker, uniting a realm that had never been easy to hold.

And at his side—never behind—stood Taytu Betul.

Descended from noble houses in the north, Taytu was sharp, educated, and unapologetically proud of Ethiopia’s independence. She read foreign treaties in Amharic, spoke her mind in court, and kept her own circle of loyal generals. [5] When Menelik appointed her as Empress, he didn’t grant her power—he acknowledged it.

It was Taytu who chose the site of Addis Ababa, who organized her own battalions, and who pushed back hardest when European diplomats came bearing ink-dipped conquest. [6]

Together, they ruled a country that was not yet fully centralized—but far from weak. It was a state bound by shared faith, ancient monarchy, and a common understanding: the outside world was changing fast—and soon, it would come for Ethiopia too.

And when it did, Menelik and Taytu would be ready.

The Treaty That Sparked a War

In 1889, with Italy still young and eager to prove itself on the colonial stage, its diplomats arrived in Ethiopia bearing gifts, compliments, and a treaty—the Treaty of Wuchale. [7] On its surface, it seemed simple: a gesture of friendship, a formal recognition of Menelik II’s rule, and an offer of international support.

But hidden within the treaty’s two versions—Amharic and Italian—was a single word that changed everything.

The Amharic version, which Menelik read and signed, stated that Ethiopia “may use” Italy in dealings with other nations. It granted the emperor an option, not an obligation.

But the Italian version used the word “must”—a shift that transformed the treaty into a declaration of protectorate status. To the European powers, this meant Ethiopia had voluntarily placed itself under Italian control. [8]

It was no misunderstanding. It was a quiet invasion by ink.

Rome wasted no time. Maps were updated. Newspapers celebrated a bloodless conquest. King Umberto I of Italy prepared to bask in imperial legitimacy.

But Ethiopia was not unaware. It was watching.

When Menelik uncovered the manipulation, his response was immediate and sharp. He republished both versions of the treaty, line for line, so the world could see the lie for itself. [9] The deception wasn’t just political—it was personal. It insulted Ethiopia’s intelligence, its independence, and its emperor.

At court, Empress Taytu Betul had already voiced her suspicions. A sharp reader and shrewd strategist, she reportedly refused to affix her seal to the treaty. Where others hesitated, she spoke plainly:

“Those who sign away their independence—from fear of war—might watch as women rise when men falter.” – Empress Taytu Betul [10]

The treaty was torn, but its consequences remained. Lines had been crossed—not just on paper, but in principle.

And from that moment on, Ethiopia would prepare—not to negotiate, but to defend.

Ethiopia Mobilizes

When the lie was exposed and diplomacy soured, Menelik and Taytu moved with purpose.

They issued a national call to arms, not as tyrants but as stewards of a shared legacy. Letters and envoys went out across mountains, valleys, and rivers—summoning Ethiopia not just to resist, but to unify. [11]

This wasn’t conscription. It was a summons to history.

Nobles were asked to bring more than soldiers. They were asked to provide grain from storerooms, mules from stables, and bullets from private caches. Weapons were still being acquired from abroad—through cautious deals with French and Russian traders—and every rifle counted.

From the Simien Mountains in the north to the southern forests of Guraghe, the response was overwhelming.

Armies began to move.

Some carried ancient spears, passed down like heirlooms. Others had imported rifles. Many rode horses or mules; others marched on foot, barefoot, across jagged rock and scrubland. They sang in Amharic, Tigrigna, Oromo, Guragigna—dozens of dialects—but moved with one purpose.

Among the leaders were men whose names echoed with weight:

Ras Makonnen, a seasoned general, and clever diplomat.

Ras Mikael of Wollo, commanding both cavalry and spiritual authority.

Ras Alula of Tigray, the “Lion of Tigray,” already a legend for defeating Egyptian and Italian forces in the previous decades. [12]

They brought their own fighters, many of them veterans, hardened by border wars and internal rivalries. But now, those rivalries were paused.

The empire was assembling—a confederation, not a monolith—but unified all the same.

By early 1895, over 100,000 Ethiopian troops had mobilized. [13] It was an army of scale, yes—but also one of meaning. It represented a rare moment when language, faith, and land converged into collective resistance.

Italy’s soldiers were trained. Their rifles newer. Their boots factory-made.

But they were marching toward something they had never faced before:

an empire awake, alert, and unafraid.

What does it mean to defend sovereignty—not just with weapons, but with unity, belief, and vision?

And if history can be reshaped in the mountains of Ethiopia… where else might it still be waiting?

For feedback or inquiries, email: contact@archivinghistory.com. We look forward to hearing from you!

Join Archiving History as we journey through time! Want to stay-tuned for our next thrilling post? Subscribe!

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok for captivating insights, engaging content, and a deeper dive into the fascinating world of history.

Source(s):

1. Raymond Jonas, The Battle of Adwa: African Victory in the Age of Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), 1–3.

2. Harold G. Marcus, The Life and Times of Menelik II: Ethiopia, 1844–1913 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1995), 12.

3. Paulos Milkias and Getachew Metaferia, eds., The Battle of Adwa: Reflections on Ethiopia’s Historic Victory Against European Colonialism (New York: Algora Publishing, 2005), 5–6.

4. Harold G. Marcus, A History of Ethiopia (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 256–57.

5. Paulos Milkias and Getachew Metaferia, The Battle of Adwa, 78–79.

6. Raymond Jonas, The Battle of Adwa, 45–46.

7. Harold G. Marcus, The Life and Times of Menelik II: Ethiopia, 1844–1913 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1995), 135.

8. Raymond Jonas, The Battle of Adwa: African Victory in the Age of Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), 29.

9. Marcus, The Life and Times of Menelik II, 137.

10. Paulos Milkias and Getachew Metaferia, eds., The Battle of Adwa (New York: Algora Publishing, 2005), 56.

11. Jonas, The Battle of Adwa, 33.

12. Anthony Mockler, Haile Selassie’s War (New York: Olive Branch Press, 2003), 42–43.

13. Marcus, A History of Ethiopia (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 300.

14. Milkias and Metaferia, The Battle of Adwa, 102.

15. Marcus, The Life and Times of Menelik II, 189.

16. Harold G. Marcus, The Life and Times of Menelik II: Ethiopia, 1844–1913 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1995), 298–99.

17. Raymond Jonas, The Battle of Adwa: African Victory in the Age of Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), 152.

18. Harold G. Marcus, Haile Selassie I: The Formative Years, 1892–1936 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 14.

19. Anthony Mockler, Rags of Glory: The Battle of Adwa, March 1, 1896 (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1971), 108.

20. Anthony Mockler, Rags of Glory: The Battle of Adwa, March 1, 1896 (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1971), 110–11.

21. Markus V. Danilovich, Italian Colonialism in the Era of the Great War: Colonial Administration in Eritrea (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1970), 85.

22. Harold G. Marcus, The Life and Times of Menelik II, 302–03.

23. Jonas, The Battle of Adwa, 160–61.

24. Harold G. Marcus, The Life and Times of Menelik II: Ethiopia, 1844–1913 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1995), 315–16.

25. Raymond Jonas, The Battle of Adwa: African Victory in the Age of Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), 212.

26. Richard Pankhurst, The Ethiopians: A History (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2001), 223.

27. Beverly Haddad, Black Harlem, Empire, and Adwa (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017), 59.

28. Paulos Milkias and Getachew Metaferia, eds., The Battle of Adwa: Reflections on Ethiopia’s Historic Victory Against European Colonialism (New York: Algora Publishing, 2005), 14.

29. Harold G. Marcus, A History of Ethiopia (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 338–39.

30. Paulos Milkias and Getachew Metaferia, The Battle of Adwa, 130–31.

Artwork Home Office Decor Canvas Art Frame-style

In 1896, Ethiopia did what no other African nation had—defeated a European imperial army on the battlefield. The Battle of Adwa shattered the myth of inevitable colonization, humbling Italy and electrifying the African diaspora. In The Battle of Adwa: African Victory in the Age of Empire, Raymond Jonas offers a vivid, multi-continent account of this seismic moment. With figures like Emperor Menelik II, Empress Taytu, and Swiss advisor Alfred Ilg at its center, the book explores how strategy, diplomacy, and vision turned Ethiopia into a global symbol of resistance—challenging white supremacy long before decolonization took root.

The Final Confrontation: Adwa

The sun had not yet risen when the Italians marched into the jaws of the Ethiopian highlands.

It was March 1, 1896. Fog blanketed the peaks and valleys of Adwa, a rugged maze of ridges, cliffs, and narrow passes. The night had been sleepless. The Italian soldiers, cold and undersupplied, moved in columns, not fully aware of where their comrades were—or where the enemy lay.

At the helm was General Oreste Baratieri, a man burdened by hesitation. He had spent weeks in indecision, fearing that retreat would cost him his career. Pushed by pressure from Rome and his own restless officers, he chose to act. But he acted with flawed intelligence, poor maps, and dangerously scattered troops.

Baratieri believed he would meet a fragmented Ethiopian force—easy to divide, easier to destroy.

He was wrong.

As the mist thinned with the rising sun, it revealed not confusion—but calculation.

Menelik II had waited for this moment with discipline. His forces were already in motion before the Italians had finished their coffee rations. The Ethiopian army—thought to be 100,000 strong—was not scattered. It was positioned.

From the ridges, Empress Taytu Betul directed 5,000 troops, including her personal guards and units from the north. She had placed them on the flanks in advance, understanding that the mountains could either choke an enemy or free one—depending on who arrived first.

On other fronts, Ras Alula, Ras Makonnen, and Ras Mikael led their wings like hammer blows waiting to fall. Their soldiers had marched for weeks. They were hungry, yes—but ready. Many had fought at Amba Alagi and Mekelle. They knew what was at stake.

At the center, beneath the imperial banner of Solomon, Menelik II stood with his generals—his command relayed by flagbearers, runners, and mounted messengers.

And then it began.

Italian units stumbled into ambush fire. Shots rang out from concealed riflemen along ridgelines. Ethiopian cavalry launched from high ground, driving spears into the gaps between columns. Italian artillery, meant for open plains, struggled to fire upward or downward along the rocky slopes. Worse, some columns were completely cut off—unable to communicate or regroup.

General Matteo Albertone was one of the first to realize they had walked into a trap. His Eritrean Askari troops fought valiantly, but they were isolated and soon overrun.

To the north, General Vittorio Dabormida attempted to flank what he thought was a smaller Ethiopian detachment. Instead, he ran into Ras Mikael’s army. Dabormida’s men were wiped out. He was killed in the chaos.

Cavalry from Ras Makonnen’s wing swept through the Italian rear. Bayonets met spears. Sword met saber. Smoke covered the fields. Disoriented Italian troops were pushed off cliffs, others captured in the high ravines.

By mid-morning, the Italian lines no longer existed. They had been shattered, surrounded, and consumed.

Over 7,000 Italians lay dead. Another 1,500 were taken prisoner. Among the captured were senior officers and field staff. Two generals were lost—Albertone captured, Dabormida dead. [24]

Ethiopian losses were real, too. Thousands gave their lives that day. But their losses were borne in unity, not conquest—defending home, not empire. [25]

When the battlefield finally fell quiet, there was no cheer. There was only the sound of wind across stone.

And a silence that no European power had expected.

Ethiopia had not only defended its territory.

It had shattered a colonial myth—in full view of the world.

Aftermath: The Treaty and the World’s Reaction

Italy was stunned. Its ambitions in East Africa had collapsed. At home, riots broke out. General Baratieri was recalled and tried for incompetence. Public faith in the monarchy eroded.

In October 1896, Italy signed the Treaty of Addis Ababa, formally recognizing Ethiopia’s independence and surrendering its colonial claims. [26]

This was more than a diplomatic reversal—it was a symbolic earthquake.

International Reaction:

In France, the press begrudgingly praised Menelik’s strategy.

In Britain, colonial officers viewed Adwa as a lesson in hubris.

In the United States, Black churches in Harlem rang bells in celebration.

In the Caribbean, sermons referenced Adwa as divine vindication. [27]

Adwa became a global beacon—a moment that cracked the myth of European invincibility and gave rise to a new vocabulary of African resistance. [28]

After Adwa: A Victory That Traveled

Adwa reshaped Ethiopia. In the years that followed, Menelik focused on infrastructure, diplomacy, and internal unity. [29] Taytu became even more politically active—opposing foreign loans, advising on military appointments, and protecting Ethiopia’s sovereignty. [30]

For future leaders across Africa and the diaspora, Adwa was proof:

Africa could defend itself.

Colonialism was not inevitable.

Dignity was not something granted—it was something taken back.

The Echo That Never Faded

At Adwa, rifles met resolve—and resolve won.

This was not just a battlefield victory. It was a cultural one. A moral one. A civilizational stand against a world order that insisted Africa had no voice.